Episode 0 | Introduction – Front and Center: The COVID EOC Podcast

May 28, 2020

Dr. Jason Moats, Dr. Rebecca Katz, Jeremy Konyndyk, and Tim Manning

Jason, Rebecca, Jeremy, and Tim offer thoughts on current outbreak, highlighting how emergency operations centers are a critical part of an effective response effort. Then the group discusses what is next to come on the podcast, including COVID-local.org and the importance of helping each other solve this crisis.

Resources:

COVID-19: A Frontline Guide for Local Decision-Makers

DisasterAWARE

Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center

Hosts:

Dr. Jason Moats

Dr. Rebecca Katz (@RebeccaKatz5)

Jeremy Konyndyk (@JeremyKonyndyk)

Tim Manning (@timmy315)

More to explore:

The Center for Global Health Science and Security

The Center for Global Development

Texas A&M Engineering Extension Service

Berglind-Manning L.C.

About COVID-Local

COVID-Local.org is a central resource to aid local leaders in the decisions needed to address the community response to COVID-19. This site focuses on the Frontline Guide for Local Decision-makers, which provides a framework to help local leaders establish effective and immediate strategies to fight the outbreak. Learn more at www.covid-local.org.

Transcript of Episode 0 Follows

INTRODUCTION SPEAKER: Welcome to EOC Community Management (phonetic), the podcast designed to help local leaders understand and implement emergency operation centers as they respond to the spirit of COVID-19 in their communities. This podcast is brought to you through a collaborative effort between the Center for Global Development, the Texas A&M Engineering Extension Service, the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University, the Nuclear Threat Initiative's Global Biological Policy Program and PDC Global. And now here is your host.

MR. MOATS: Hello, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to our podcast. My name is Jason Moats. I'm the Associate Division Director at the Emergency Services Training Institute at the Texas A&M Engineering Extension Service. And I am pleased to be joined today with several subject matter experts from around the country who are very interested in how EOCs run and things that we can do during the pandemic. Our podcast today is just kind of an intro to introduce you to what we're going to do and to talk to you a little bit about our backgrounds and everything else. So, we're going to start with some brief introductions and I'm going to hand it off to Jeremy Konyndyk.

MR. KONYNDYK: Thanks, Jason. Hi, everybody. It's great to be speaking with you today. My name is Jeremy Konyndyk. I am a senior fellow at a research institution in Washington called the Center for Global Development and I come out of a career in emergency response and humanitarian management. And my angle on this whole issue is, I spent about 3.5 years during the Obama administration working as the director of foreign disaster assistance at USAID. So, I was sort of running the U.S. Government's international equivalent of FEMA and in that role ended up managing a lot of the U.S. Ebola response in 2014 and '15 and had quite an odd, but very educational experience as an emergency manager, more accustomed to natural disasters and humanitarian response, finding myself managing a disease response and having to adapt a lot of kind of my team's rhythms and my own understanding to the ways in which an outbreak response is different from the sort of responses that we were used to managing. And since then I've also been working as an advisor to and an overseer of the emergency response program at the World Health Organization, which has been closely involved obviously in this effort.

And so very, very glad to be speaking with all of you today and hope to share some of the lessons that we've learned over the years and help bring the country through this big challenge we're facing.

MR. MOATS: Hi, Jeremy. Well, thanks a lot. This is going to be a great conversation with you.

Now I'm going to ask Tim Manning to introduce himself. Tim?

MR. MANNING: Yes, Jason. Yeah, Tim Manning here. I'm currently the director of Washington D.C. operations for applied disaster and crisis research organization called the Pacific Disaster Center, PDC Global. It's based in Hawaii. I'm based here in Washington D.C. I had the good fortunate of spending 8 years as a deputy administrator of FEMA for protection and national preparedness, spent a decade before that as a homeland security advisor and state director, emergency management for the Governor of the State and a first responder EMT, firefighter and I've worked the gambit across the emergency management world and, you know, across that career had a lot of opportunities to work in disease outbreaks, involved in the domestic side of the Ebola crisis that Jeremy was referring to. Yeah, what are we doing with the support, first responders and hospitals when there were cases in Dallas and when we had workers coming back from West Africa.

Of course we -- FEMA, we also had dealt with H1N1 in 2009, the Zika outbreak in later and countless -- the pandemic disease outbreak exercises over the years. Conducting them and working with mayors and governors, presidents, the transition exercises, and all of that planning and I think what we've seen through all of those exercise and all of that planning is that unfortunately none of this is a surprise, kind of the way that this disease is breaking out is pretty much as we've exercised and planned for over the years. The magnitude is, I think, a bit more than we expected and I think we have a lot of opportunities to kind of learn from what we thought might happen and build on that.

So, excited to be here and very happy to be talking with some of our colleagues here. Thanks.

MR. MOATS: Thanks, Tim. And we're also joined by Dr. Rebecca Katz. Rebecca, welcome.

DR. KATZ: Thanks, Jason. So, my chance to say a little bit about myself, I guess. I am a professor at Georgetown University where I direct the Center for Global Health Science and Security and I also teach a lot, mostly in the School of Foreign Service, but I teach courses in emerging infectious diseases, global healthy security and health diplomacy.

I've been working -- well, Tim's description of what he has done in his career reminded me that I was once upon a time EMT and a really bad firefighter. But that was -- that seems like a lifetime ago. I spent most of the last 20 years working on issues related to pandemic preparedness and global health security, mostly from a policy perspective, but always as a public health professional. And that's ranged from work we did as implementers for CDC -- U.S. CDC primarily in Guinea during and immediately following the West Africa Ebola outbreak. That has included work for about a decade looking at urban health security and thinking about the flow of risk, but also working with the Global Parliament of Mayors for the last few years thinking about how municipal level leaders need to be organized for addressing infectious disease spread.

And that's -- a lot of that work is actually in forums, the work that we're doing right now with COVID Local and thinking about the role of municipalities in trying to respond to this current pandemic. And then also spent about 15 years as a public health expert consultant at the U.S. Department of State, primarily promoting the biological weapons convention, but in that capacity very much focusing on Article VII, which is preparedness and response. So I've been thinking a lot about the preparedness and response aspect of large scale infectious disease outbreak for a really long time.

MR. MOATS: Well, thank you, Rebecca. And again this is Jason Moats. As I said, I'm the associate division director at the Emergency Services Training Institute here at TEEX. And I come from this -- come to this from a really different angle. Like Tim and apparently like Rebecca, I was at EMT and a really bad firefighter. And -- but that was, you know, a long time ago. However, I grew up in rural Indiana and one of the things that sparked my interest is I came into, especially in the post September 11, 2001 era, was the vulnerability that we have within our agricultural system in the U.S. and that got me to thinking, there was some work that I did while I was at the Kentucky Division of Emergency Management and later here at Texas A&M, about how vulnerable we are from not only an animal health perspective, but a public health perspective and, you know, what would happen. And so I was fortunate enough to work with folks from around the world in looking at those kinds of things.

But my heart always goes back to those farmers that are sitting there and doing those things and how utterly devastated they would be if we had an event here. So, I have spent the vast majority of the last 25 years working on providing training and education to our emergency managers around the world to look at this. And so when the opportunity came up for being able to do this podcast, it just seemed natural to come together with this great group of folks and talk a little bit about the things that we can do in our local EOCs in the midst of the things that are going on, but also in the planning and the preparation for that next thing to go on.

So, with all of that said, our format for this is fairly open today. And what we're going to do is just talk a little bit about the different things that go on. And so I want to talk just briefly about COVID Local and what's that all about. Jeremy, can you talk a little bit about that?

MR. KONYNDYK: Thanks, Jason. Yes. COVID Local is an initiative that my institution, CGD, along with Georgetown and the Biological Threats Division of an organization called NTI put together because we saw a gap in the guidance that cities and localities were receiving. You know, we've seen in past outbreaks, really in every past outbreak that decisions that are made at a city and locality level have a real impact on the trajectory of the outbreak in a community, you know. So the federal level is very important, the state level is very important. But, you know, a lot of -- where the rubber hits the road is really at that city and community level. And the kind of classic example of that is from the 1918 influenza pandemic where the cities of St. Louis and Philadelphia had hugely different experiences with the same virus because St. Louis acted very early to begin physical distancing and Philadelphia waited and held a big -- notably held a very big parade and ended up having a much worse outbreak because they were not taking measures early.

So that -- you know, the quality of local decision making has a huge impact. But we were also struck as we were, you know, as we were talking to people from mayor's offices and county officials, they -- you know, they weren't trained to do this, they weren't getting a lot of support and guidance. Most of the support and guidance is focused on other levels of decision making. And so we saw a gap there. So, we put together the COVID Local tool, which is focused on enabling policy makers at a city and community level to know what questions to ask, to understand how to organize themselves and how to adapt some principles of outbreak management and emergency response to what they're facing with this outbreak in their community.

And that hybrid of an emergency management approach and an outbreak management approach is really important and that's central to the COVID Local tool and central to what we want to try and do with this podcast series because, you know, one of the experiences that I and my team had during the Ebola outbreak, you know, we were all disaster managers, we were used to dealing with hurricanes, famines, and things like that and this was a very different kind of rhythm, it had a very different kind of organization than what we were used to. But the skill set that we has of -- and we didn't the sort of infectious disease skill set that the CDC had, but by pairing up what they had with what we had, which was really, you know, the operational capacity, the coordination capacity, the ability to use different streams of information and turn that into operational decision making and action, you know, that was a really powerful combo.

But we initially didn't know we didn't know and so we had a lot of learning on the job. And as we kind of found our rhythm, figured out how to do this and worked closely with the infectious disease experts at the CDC. It turned into a pretty powerful combo. So, we are hoping that with the COVID Local tool, we can help others skip some of those, skip forward a few of those steps, understand from the beginning what kind of decisions they need to be making and what kind of questions they need to be asking.

MR. MOATS: That's great. Tim, Rebecca, would you like to add anything?

DR. KATZ: I would -- I will actually just add in that to -- we've actually been -- we've been really -- one of the things that my research team does is we actually try to create the evidence base behind a lot of the decision making that's happening in health security and specifically in pandemic preparedness. And one of the questions that we had been asking for a couple of years actually was trying to figure out how much preparedness planning was happening at the city level. And so -- and we knew that there were national level pandemic preparedness plans in those countries, like almost all, even as most, many hadn't been updated in over a decade. But there are -- there were country level planning, but very seldomly were there -- and in the United States there were often state level plans, but there are almost never city level plans. And in fact we were actually studying all the megacities in the world to figure out which, you know, which city of 10, 20 million people actually had a plan and most didn't. And so one of the things that really struck us at the beginning of this pandemic was everything we always kind of feared and knew from smaller scale of events that it's often the municipal level leaders who had to make the decisions of, you know, how or if they're going to do a quarantine, whether they have to close schools or not, where the vulnerable populations are.

All the different -- and be able to translate the guidance that may or may not be coming from a higher level of governance to their own population. So, we were very struck about the need to try to move something forward. And to Jeremy's point, we were getting requests, we were -- there were a lot of leaders who were just -- didn't quite know what to do next and I think were struck -- they were struck by the lack of guidance that they were getting and we were struck that we were like, well, where is all the guidance, who -- why isn't somebody else doing this. So, we're trying to -- we're trying to fill the gap and hopefully trying to do some good with it, but also learning as we go. So, you know, we were able to put some material forward, but that's not the end of it. We're now trying to, again, try to build that evidence base, collect best practices, coordinate with our colleagues from around the world and particularly around the country, but also around the world and try to figure out what's working and be able to package that and give it back to other municipal level leaders.

MR. MANNING: This is Tim, and I will jump in if I -- after hearing what Rebecca says and I think what she found in looking for pandemic response plans at the municipal level around the U.S. anyway is mirrored by kind of the capacity for emergency management generally at the municipal level. There are very well experienced, dedicated people all across the country working at the city level, at the local level, city, county, parish, across United States, but almost universally under-resourced and strapped, right? There are crises that break everyday that they're dealing. Most emergency managers, I think, you'll find have a pretty good sense of the suite of hazards, everything from pandemics to acts of terrorism and natural disasters that are facing their communities, but very rarely have the opportunity and the resources, both financial and human capital, to be able to do much about it, to put plans into place and be able to have that. And a lot -- and oftentimes the guidance that does come down from the health -- Department of Health and Human Services and FEMA and CDC and the States is hard to actualize at the municipal level for many reasons, not the least of which is that health governance is different in every state. In some -- it's at the state level some places, at the county level other places, at the local level other places.

So, generalized guidance is hard to -- hard for a part time emergency manager or the one full time emergency manager working for a mayor with no staff to put into place. So, efforts like these, I think, are invaluable as kind of just in time guidance and tools to help the mayors, their teams, the local emergency managers, the police chiefs, CMS chiefs, fire chiefs, the public health folks to be able to come together in a novel crisis and apply the tools that they use on a day-to-day basis in a new and creative way.

MR. MOATS: Jim, I think you're absolutely right. You know, it's a struggle when you're working through those, you know, those competing priorities in that city and, you know, you're balancing between where you sit on the wildland-urban interface and worried about the fire or the next ice-storm or the next thing and then all of a sudden here out of the blue almost comes this disease that nobody has ever seen before, we know nothing about and, wow, the impact that it has had and it's challenging. So, you know, Rebecca, I want to come back to you just for a second. You mentioned a phrase before that I'm not sure everybody knows which is, you talked about health security. Can you talk a little bit about what health security is and what that means?

DR. KATZ: Great question. And there are a lot of people who have been working to try to define it. I think the easiest definition and to be honest, Jason, the taxonomy has changed over the last 20 years. So, a lot of what we call health security today is what we called public health emergency preparedness before. But overall, really what we're talking about are the plans, the policies, the systems required to be able to prevent, detect, and respond to public health emergencies regardless of origin. So, it is everything from thinking about the global governance of disease outbreak to capacity building to the workforce required to be able to link both public health infrastructure and disease surveillance with things like emergency management and then also to actual healthcare as well. So, it's a -- it is basically what we used to call public health emergency preparedness.

MR. MOATS: Great. So, we've talked a little bit about these tools. Tim, you mentioned it, Rebecca, you've mentioned it. Where can, if I'm sitting at my local EOC, where can I go and find some of these tools?

MR. KONYNDYK: So, within the COVID Local toolkit and the website for that is just covidlocal.org. Within the COVID Local tool, we've got a set of, you know, key actions that we recommend and that's things and, you know, I won't run through them all now, but we'll talk about a lot of them in these podcasts, you know, things like how to organize your EOC, how to access and understand the information on how the outbreak is behaving in your community. And so we have some keys questions to ask yourself as a way to kind of just run a checklist of whether you thought through the different angles that might, you know, that might arise over the course of this outbreak. And then there's always the resources, so for each of those, there are key resources that you can look to for further information if there are questions you have and also through the COVID Local website, we have an address where we're taking questions and can provide feedback to people if there are specific issues that need further clarification or, you know, questions on how to put things into action. Sorry, the sidebar, Jason, is this where you -- are you going to kind of cut away seasonality stuff here as well in terms of recommendation (cross talk)?

MR. MOATS: I wasn't. So, hang on just a second.

MR. KONYNDYK: So, those are some of the ways that we're capturing resources in COVID Local and we will be updating the website regularly as well with additional content both with further resources and we're also inviting notes from the field where people have a chance to share some of the experiences and lessons they've learned and we will post those as live post on the site and continue kind of building out that content as there is more learning emerging from how this virus is being managed. Tim, I know that you and PDC have done some work to develop resources on this as well.

MR. MANNING: Yeah, thanks Jeremy. The, you know, the information needs in this particular crisis in the Coronavirus outbreak are unique for local EOCs. There are a lot of sources of information, sometimes good, sometimes bad. One of the things PDC does as applied research center is pulling authoritative data sources from all over the world, government agencies, the whole universe of various government agencies, multilateral organizations, multinational organizations and in this case, a special effort around COVID-19, pulling in information, working in partnership with the Department of Defense, the Department of Health and Human Services, FEMA, the National Emergency Management Agency and a number of other organizations. To make all of that information, all of those authoritative sources available and modeling predictive tools available on our common operating platform system, disaster alert. It's available at pdc.org. Anybody in the public can get access to the public version. If you're a local emergency manager or state, if you're working in emergency management or in any of the affiliated fields and supporting this response, you can also click through and request access to the professional version called EMOPS, that's a government response version. It's all free, it's entirely paid for by the Department of Defense, so it's completely free to the user and that's a tool that's hopefully of use to emergency managers all across the country.

MR. MOATS: Thanks, Tim. That's great news to have, you know. I think that's it's, like I said, it's really important that not only do we know about the tools, but we know where to go get them. And so this -- our -- the website covid-local.org is really important to being able to be one of those places we can go and then as Tim said with what the PDC is doing, that's -- that provides a lot of information. So, you know, we -- kind of the impetus behind this is, we're in the midst right now today of this pandemic that has taken over globally and, you know, we've been at it for a while. And it's important that we talk about what we can do to help each other to get through this. And so we all came together and looked at what we could do and the information we can provide.

So, what I'd like for us to do now if you're all willing is, let's talk a little bit about what folks can expect to hear from us in the future. So, you know, for example, Rebecca, I know that you and several of your folks there at Georgetown have been doing a lot of work with analytics in a pandemic. Can you talk a little bit about that and how that might help in the EOC?

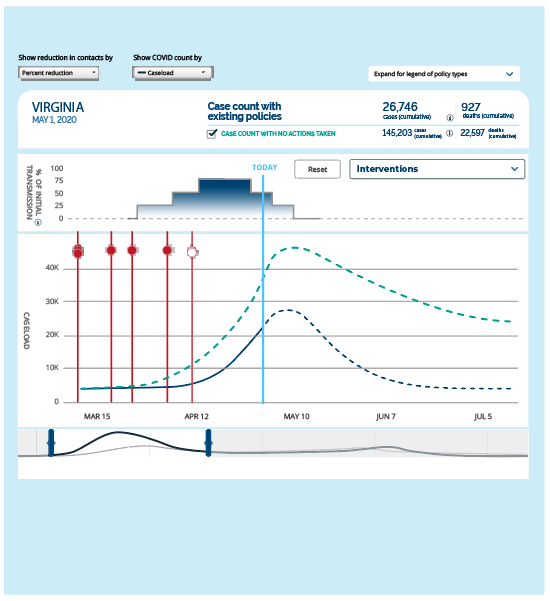

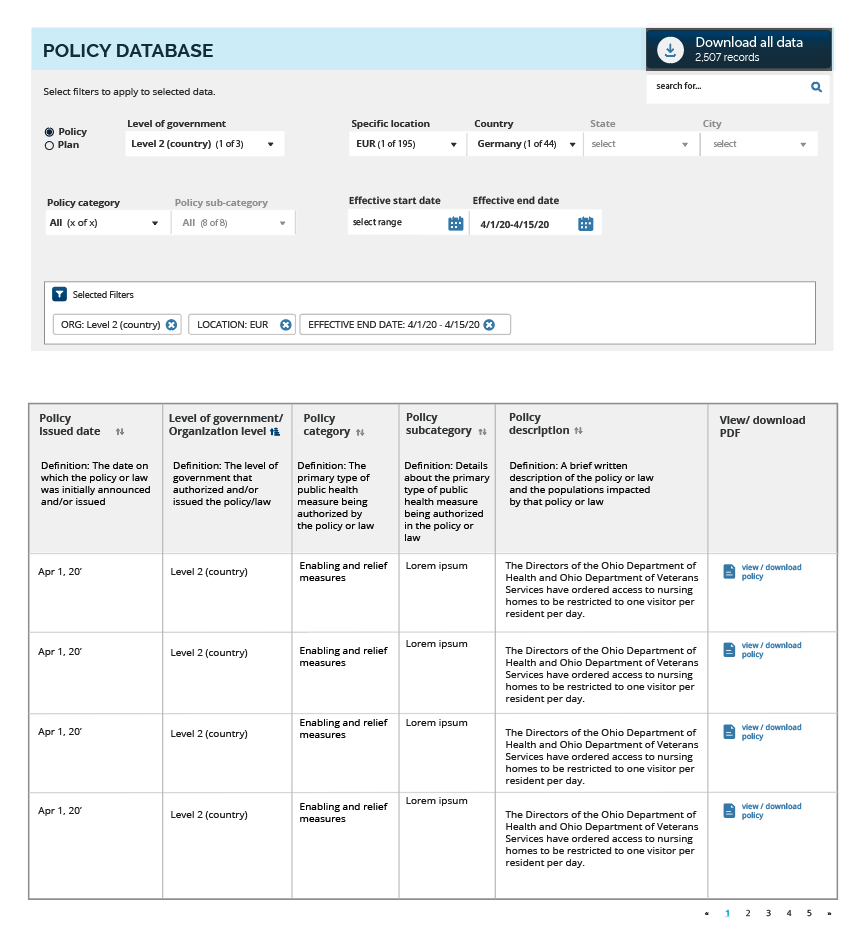

DR. KATZ: I can do my best. I think, you know, the -- EOC is reliant data, I mean, you need data coming in, in order to make good decisions and coordinate the information and go on from there. As we all know, there is a lot of models out there, some of them are helpful, some of them are less helpful, some of them are more helpful just for a direction of the outbreak. But I think that a lot of people who are struggling to figure out, you know, where are the data, there is a lot of questions that have to be answered. And one of the challenges is trying to identify where that data are going to come from and then how it then feed back into their operational decision making.

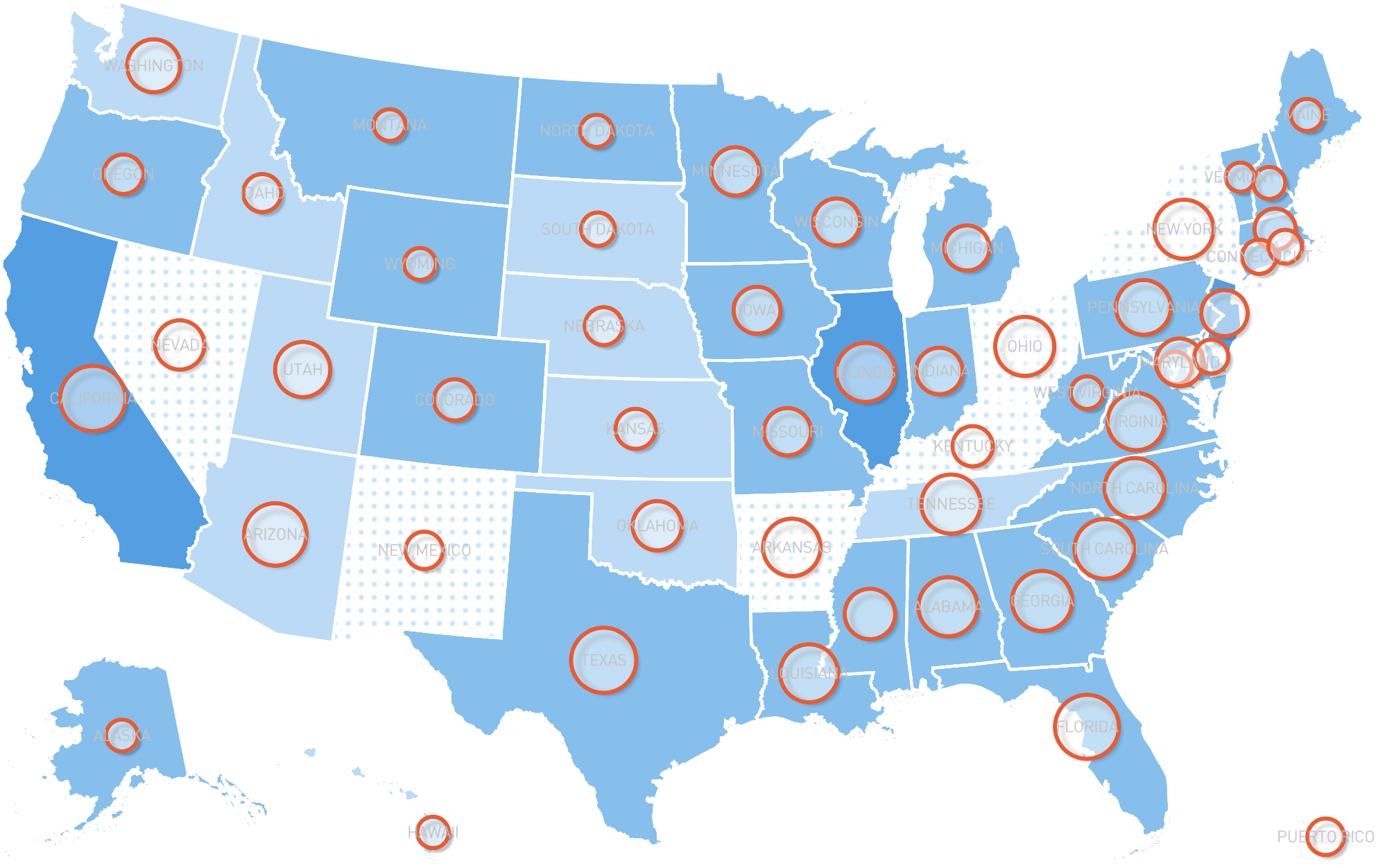

So, and one of the things that we're trying to do is look at all of the models that are out there, looking at all of the data that are coming in and trying to distill down to what are the pieces of information that are needed specifically for decision making. And so we're looking at not just the analysis of all the academic goals that are out there, but also trying to build out some decision support tools and to break down into -- and it's pretty simple questions, you know, what -- here are the questions that we need to answer, here are the data and linking back to the data sources that are clearly coming online to be able to try to answer.

MR. MOATS: That's great. Jeremy, can you talk a little bit about may be how we organize the EOC because I think that will be something that's really important too because you mentioned that this is different than a hurricane, this is different than that ice-storm that hits the mid-west. So, talk a little -- can you talk a little bit about that?

MR. KONYNDYK: Yeah, you know, I think, you know, one of the really important things to understand right from the outset here is that the kind of the rhythm and the pacing of this sort of, I mean, that's very different. And that was a big learning curve for me and for my team during the Ebola outbreak that, you know, we were used to something like a hurricane or an earthquake where you go really, really hard for, you know, a few weeks, may be even for a month or two. But, you know, after the event has begun, you know, the event happens, it hits, and then you're moving immediately into a recovery mode. And, you know, with an earthquake, there might be aftershocks, but, you know, an earthquake is not contagious, a hurricane is not contagious. And so once you're through the main event, you're through the main event and then you're moving onto other things. And it's a very, very different sort of rhythm with an outbreak. You've got actually -- you've got a sort of slow build at the outset and that's what we saw or, you know, kind of what we failed to see unfortunately in this country through February about what was happening in this country from February. This kind of slow build that then suddenly accelerated very, very rapidly in March.

And, you know, we're now looking ahead to a period, I think of, we're going to see a long plateau in cases and we're starting to see that in New York City, we're starting to see that in some parts of the west coast that were on the frontend of this outbreak and we've also seen that in some of the other countries that have been affected, Lombardy in Italy had a very fast rise and a much longer, slower decline in case levels. But then once you bring that, you know, once you bring those numbers back down, it's not over. We're going to be playing a game of whack-a-mole against this virus for the next 2 to 3 years until a vaccine becomes widely available and hopefully that's closer to 2 years than 3, but, you know, that we don't know yet. So, even once the curve comes down the first time, there is always, you know, it's like a -- it's a little -- I think, you know, thinking of a disaster management analogy here, I think it's quite closest to a forest fire that the longer, you know, kind of the longer you wait trying to contain a forest fire, the further the fire spreads and the further (inaudible) it gets. And until as long as there are sparks out there and as long as there is dry kindling out there, you are not safe. And it's a little bit the same with the pandemic that the, you know, as long as we have a susceptible population in a country and where, you know, we have that right now and as long as there is some degree of transmission ongoing, you've got to be very vigilant even once that kind of main fire is contained, if there are still sparks shooting off from here and there, there are still hotspots here and there. You know, you've always got the possibility of another resurgence and you've got to jump on that really quick. And so, you know, we're going to have this long, you know, this multi-year game of COVID whack-a-mole for a couple of years.

MR. MOATS: So, Tim, I will ask you, you know, what value or what do you see us doing for kind of bringing in how things relate to the local from the national and the international?

MR. MANNING: Yeah, that's a great question. And, you know, as Jeremy was mentioning, this is -- this is not like anything we've dealt with before from emergency management from a state, federal, local, the large, the Big Ten Emergency Management, all the partners. We've -- look, honestly, we as a nation, we as a kind of global community haven't dealt with anything like this since the, you know, 100 years. And it's probably more severe than it was even then because of the global economy, because of the interconnectivity of communities, our communications, you know, it's something that we've never had to face. And it's -- and it's going to last for a long time. You know, there is no emergency operation center in America, in the world that's going to be -- that using the systems that were in place 3 months ago can maintain the operational tempo it's going to need for the next 18 months to 2 or 3 years.

You know, best case scenario is a vaccine developed out in the field in the next year, year a half, but then we've got to get some number of billions of people in the planet, you know, vaccinated. It's going to take a long time and we're in this for the really long haul. So, it's going to require a level of partnership between the federal, state, and local levels and a level of partnership amongst the various levels, the state and local governments through mutual aid. That we've talked about may be in the margins of other meetings, but never have had to do before. I mean, ask yourself as a local official, how are you going to maintain the operational tempo in EOC for 24 months. What are you doing today for the next 2 years? Where are you going to get those resources?

Now that's -- there are things, we do supply chain, we do logistics, that's what emergency management is, we can get stuff from where it is to where it's needed. But now we need testing, we need testing materials. We need to coordinate personal protective equipment. There is going to be -- and that's going to happen at the local level. Your local EOC -- your local EOC is going to need to know what's the ICU bed availability at the local health center. You know, that's not just a FEMA, HHS thing, that's a mayor thing too. In order to get the equipment, the responsiveness you need out of the state and the state out of FEMA, out of the federal government, every one of those layers is going to need to know that priority need because everyone is in competition with each other. You know, not a market competition hopefully, you know, will get into a steady state, but it's going to be priority, right. When FEMA has got to decide is, is Baton Rouge going to get this or is Tulsa going to get this. This is going to require a level of connectivity that we've never had to face before.

MR. MOATS: Thanks, Tim. You know, I've got a colleague that likes to say that emergency management is a team sport and I think you -- you hit it around the head. It's a crosscuts and the enormity of what we're facing right now is almost overwhelming. But I think as a local emergency manager is that person sitting in the state operation center or sitting in those regional resource coordination centers around the country, we don't have the option to give up. It's we've got to figure out how to work through this and it's going to take solutions that we've never thought of before and it's going to take teamwork in ways that we've never done before.

And so hopefully what we're doing with this podcast and the series, the follows. We'll provide some insight, some help, and then let everybody know that you're not alone. We're sitting here, we will introduce some of the brightest scholars that are not locked away in ivory towers, but are down in the trenches as well that are looking for these evidence based solutions of things that were not in some theoretical vacuum, but on the ground, really working on improving. So, we hope that you continue to tune in. We hope that this is of some use to you folks out there and by all means, please reach out to us through the covidlocal.org site or through the information we have pasted in here. So, folks, we are just about out of time. I want to ask my colleagues; Rebecca, Jeremy, Tim, do you have anything to add as we sign off?

MR. MANNING: Jason, I think the only other thing I'd say is, you know, this is a crisis that will be addressed in part through people's behavior and people's choices. And so one of the really important things that needs to happen at a community level is good communication on risk so that people can be making informed, wise choices about their own behavior because, you know, this disease spreads from person to person and it spreads through those interactions. And so if people are making good choices, minimizing those risky interactions, adapting their behavior, that is a large part of how we will beat it.

MR. MOATS: That's an excellent point. Well, friends, thank you for joining us. It has been an absolute pleasure to hear you all talk and until next time.

SPEAKER: Thank you for tuning into our podcast. This podcast series is brought to you through a collaborative effort between the Center for Global Development, the Texas A&M Engineering Extension Service, the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University, the Nuclear Threat Initiative's Global Biological Policy Program and PDC Global. Thank you and stay safe.

LIST OF PARTICIPANTS:

JASON MOATS

Associate Division Director Emergency Services Training Institute Texas A&M Engineering Extension Service

JEREMY KONYNDYK

Senior Fellow Center for Global Development

TIM MANNING

Director Pacific Disaster Center

REBECCA KATZ

Director Center for Global Health Science and Security Georgetown University Medical Center