COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter Protests: Local Government Responses Restrict Rights, Increase Risk

Jun 18, 2020

Madison Alvarez

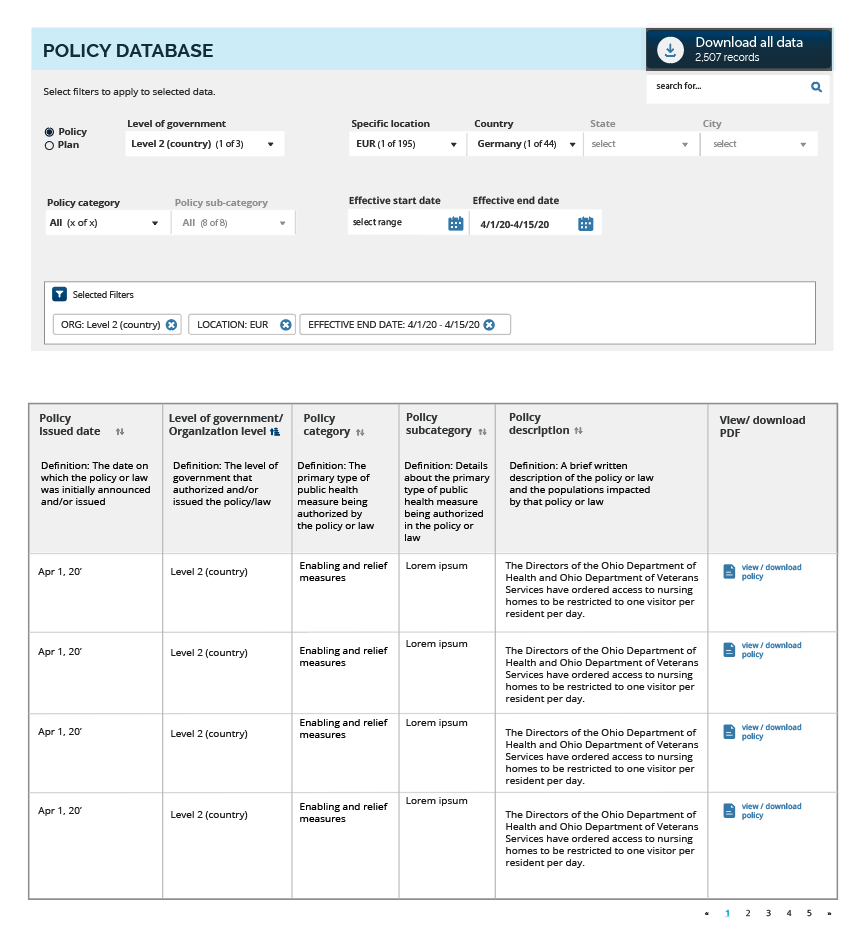

The national Black Lives Matter protests that erupted following the murder of George Floyd call for a re-imagining of the role and powers of policing and the disproportionate impact police violence has on Black and Brown communities. Importantly, they forthrightly identify racism as a public health crisis. While the Black Lives Matter protests play an essential role in calling attention to vital health needs in the United States and globally, the current COVID-19 pandemic puts the health of protesters and their communities at significant risk. In response to these demonstrations, many governments have enacted new policies that have reduced individual, local, and state capacity to implement measures to address risk of increased COVID-19 transmission.

Curfews Crowd Detention Centers and Close Testing Sites

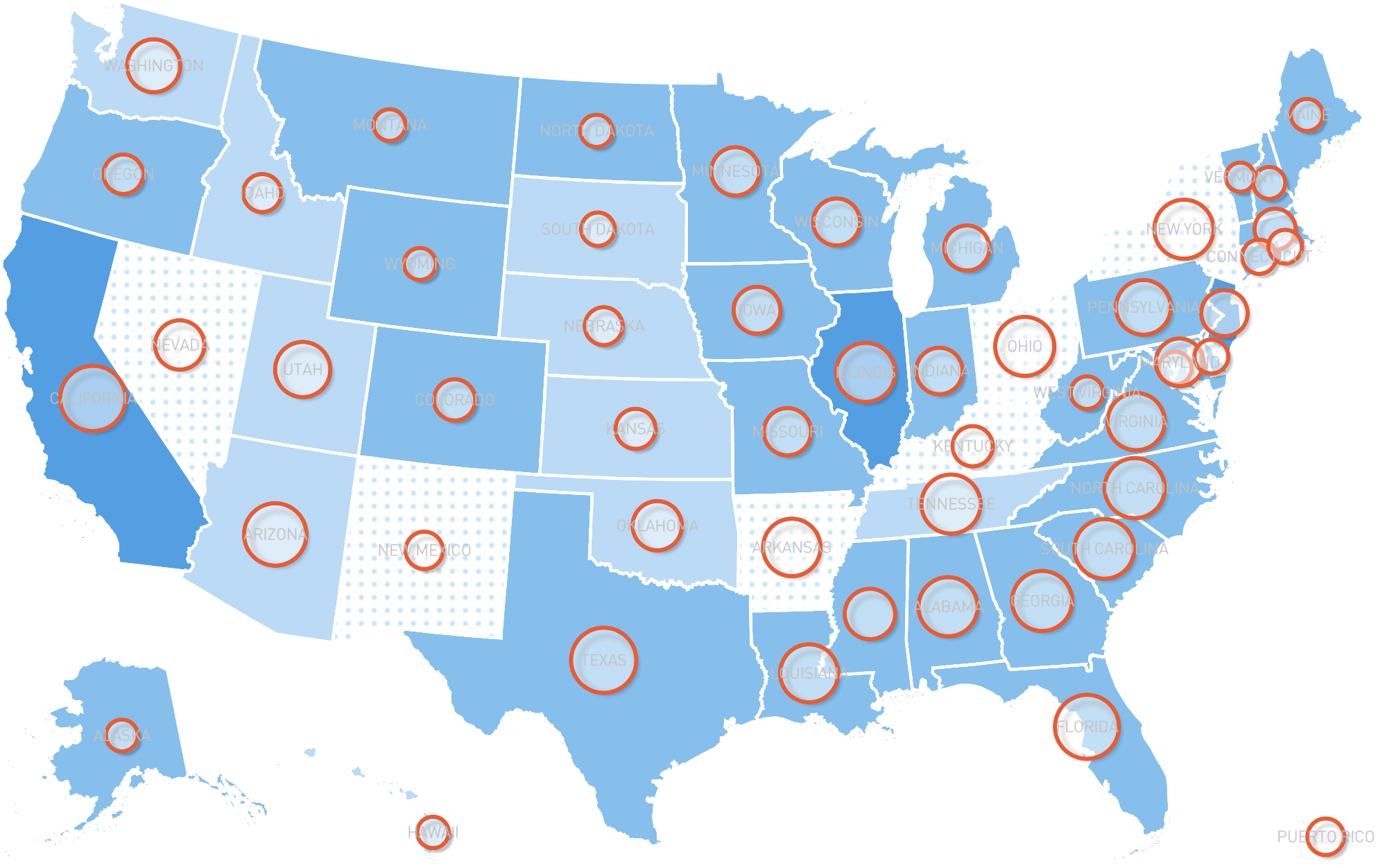

In the early days of protests, eighty cities across the country and the entire state of Arizona implemented curfews with the goal of limiting the protest hours. Most localities set curfew areas in local downtowns, especially around city halls and police stations, where most demonstrations were being held. Curfews forced the closure of many essential businesses and COVID-19 testing sites, cutting off protesters and their local communities from health services when they most needed them.

Violations of these curfews instantly became the leading source of protest-related arrests, contributing to jail overcrowding and breakdowns in physical distancing. Washington D.C. police arrested 325 protesters for curfew violations over the four days restrictions were in place, constituting 63% of all cases during that time. Days into Dallas’ curfew, police implemented the crowd control method of kettling, using flash bangs, smoke cannisters, and less lethal ammunition to crowd 674 protesters onto a freeway bridge. They then sealed off both sides of the bridge with SWAT teams, officers in riot gear, and squad cars. When curfew struck, every protester was instantly detained, causing them to remain in close quarters for hours while their arrests were processed. Similar trends in major cities across the nation suggest that curfews are the leading cause of mass arrest and resulting overcrowding, putting protesters at increased risk of COVID-19 exposure.

Where weakly enforced, curfews merely shifted protesters into locations that were indoors or far more crowded, reducing physical distancing significantly. In Phoenix, locals realized within a week that curfews were only being enforced against protesters, allowing many downtown businesses to remain open past the 8:00 P.M. restriction. Local bars then chose to remain open as late as 2:00 A.M. to serve food to protesters as they were forced off the street. Reports of large crowds squeezing into these bars for hours at a time prompted concerns that the Arizona curfew ultimately increased the risk of exposure for Phoenix protesters, as well as the employees and local customers they encountered. In the wake of condemnation by advocates, including protesters themselves and the ACLU, many curfews have been lightened or lifted as of mid-June.

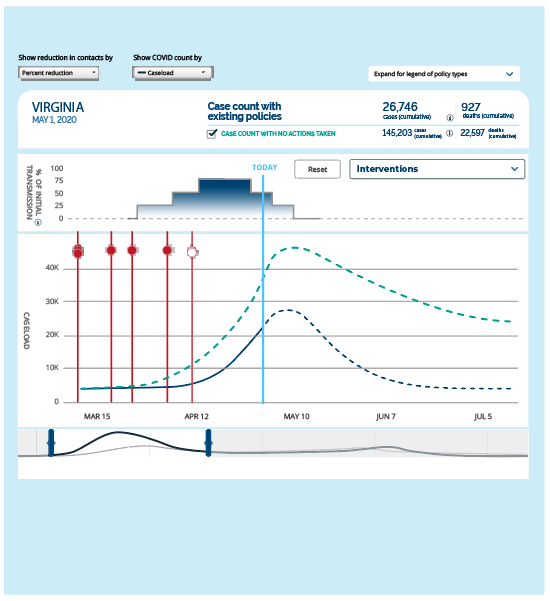

Priorities & Resources Shifted Away from Testing

Though many localities closed their testing centers in response to curfews, other closures were related to reallocation of National Guard resources that had previously been supporting COVID-19 response. Los Angeles closed all its testing sites on June 6th, shifting National Guard resources away from testing centers to the front line of the protests, and reopened only two on June 8th. Illinois shut down all of its sites on June 1st and 2nd, citing protests in Chicago. Philadelphia, San Francisco, Jacksonville also closed scores of sites. These closures, even for limited periods of time, have posed a serious threat to the ability of health systems to identify and respond to potential future increases in incidence. The failure to adequately resource testing centers, and to exempt travel to testing centers from curfews, poses a significant threat to surveillance measures in a time when they are most needed.

Chemical Irritants Facilitate Transmission

During protests, the use of “riot control” chemical weapons by police is a source of concern for the health of protesters. The danger posed by these agents is such that they have been banned for use in warfare by the Chemical Weapons Convention, which the United States ratified in 1997. The use of pepper spray and tear gas harms respiratory systems and weakens immune response, helping to trigger infection among those exposed. Because they also result in crying, screaming, and coughing – all of which are associated with increased transmission - these tools have been condemned as a “recipe for disaster” for the fight against COVID-19 by Sven Eric Jordt, who researches the effects of tear gas at Duke University. Despite these impacts, there have been numerous reports of police over-using these chemical agents, and in unjustified circumstances, against protesters. While data are not being systematically collected on how often tear gas and pepper spray have been used against Black Lives Matter protestors, or in what contexts, further research into their impact on COVID-19 exposed persons – and reviews of their application in non-riot settings – is warranted.

Mass Arrests Endanger Protestors

In the ten days following George Floyd’s death, some 10,000 people were arrested in protests across the country. While some charges for arrest include theft and violence, most of the arrests have been for low-level offenses such as violating curfew violations and failure to disperse. While most of those arrested at protests are released soon after processing, those who are jailed in overcrowded facilities are put at further elevated risk of contracting COVID-19, as jails generally lack the ability to provide proper physical distancing and sanitation measures. Individuals who contract COVID-19 while incarcerated may then spread the pathogen upon release.

To reduce crowding and the potential for associated spread of COVID-19, community advocates have organized funds to support the release of those arrested during protests. Generally conducted entirely online, these bail funds are community organized, crowdfunded pools of money to post bail for arrested protesters. A list of these funds has been compiled by the National Bail Funds Network.

Legal societies have also begun suing cities for the mass release of protesters due to delays in processing, concerns about the justification for their arrest, and health concerns related to COVID-19 transmission in overcrowded jails. This generally frees incarcerated persons from the requirements of bond, but not necessarily the charges levelled against them. In New York, the legal aid society brought a suit for the release of 108 people recently arrested and held for extended periods due to delays in processing. In Texas, Governor Greg Abbot passed new measures to limit release from jails during these protests, which, following lawsuit, a state district judge blocked. Measures to reduce the jail population are likely to stem the spread of COVID-19 among those arrested and the often-vulnerable communities to which they return. Epidemiological studies of new case numbers detected over June, if associated with detention history, may further understanding of these dynamics.

Local Governments Have the Power – and Duty – to Mitigate Transmission Risk Among Protestors

Fundamentally, local governments and police forces have a Constitutional duty to preserve the First Amendment rights of protesters. Most response measures to date have neither preserved these rights nor achieved their stated goals of preserving public health and safety. To date, state and local responses have been dominated by a fear of escalating violence. While perception of the Black Lives Matter protests – whether as gratuitous riots or justified peaceful demonstrations – has been turned into a partisan issue, transmission of COVID-19 throughout these communities does not adhere to party lines.

Local authorities can begin improving their community’s health and safety by acknowledging publicly that Black Lives Matter, and, especially during the month of June, that Black Trans and Queer Lives Matter. But these efforts must not stop at words alone. There is an urgent need, and available opportunity, for local governments, state politicians, police, and health systems to adapt their protest response policies to better protect their own communities in the coming weeks.